On 16 September 2025, ahead of the ADR UK Conference in Cardiff, Ludivine Garside (University of Oxford), Lola Brookes (ADR UK), Giulia Mantovani (NHS England) and I (Joseph Lam, UCL/NHS England) convened a pre-conference workshop on communicating about the quality of linked data.

Our aim was to bring together researchers, data owners, linkers, funders, and the public to discuss how we can better understand, document, and share information about linkage processes—an essential step in building trustworthy, high-quality administrative data research.

The data-to-evidence pathway

We began by situating linkage within the broader data-to-evidence lifecycle. Administrative data do not arrive in research-ready form; they pass through a pipeline of data capturing, linkage, cleaning, and transformation before reaching the stage of analysis and interpretation. Multiple decisions were made by different people, for different reasons at each stage, which may introduce potential biases and blind spots.

Participants reflected on four key sources of bias:

- Pre-processing bias – introduced by selective transformation, harmonisation, and assumptions

- Data quality issues – unequal error rates and systematic recording differences across groups. Partially explains the variation in linkage rates by population groups, such as ethnicity.

- Methodological bias – arising from technical linkage decisions. For example, choice of similarity metrics may interact with variations in data quality; blocking rules requiring complete addresses may be more likely to exclude people with no fixed abode.

- Sampling and linkage bias – linked to data exclusions, data opt-outs, linkage biases. This describes the demographic difference between expected population and linked population.

The data and evidence generation pathway is not linear. Evidence generated through analysis should feed back into data stewardship, improving the quality and inclusivity of future datasets. But too often, the feedback loop remains weak or under-utilised. Among our participants, most experience lies in recognising sampling bias in the linked data, while there is far less clarity on the other sources of bias, on whose responsibility it is to act, how they are communicated along the data generation pipeline, and on how practical remedies should be implemented. This uncertainty leaves important gaps in accountability and hinders systematic improvements across the data lifecycle.

The good, the bad, and the ugly

To ground these concepts, our guest speakers (Dr Kate Lewis, Rebecca Langella) and co-chair Ludivine Garside shared their experiences illustrating how linkage shapes both the data available and the conclusions drawn. Understanding national data opt-out within ECHILD highlighted how exclusions can constrain representativeness; linkage gaps in Children Looked After data with National Pupil Database showed the limits of linkages across services. Most strikingly, in Ludivine’s project, issues of poor linkage quality only became visible and communicated in the 12th month of a 15-month project, leaving little opportunity for correction or mitigation. These examples underscored both the value of linked data and the risks of working with incomplete, biased, or poorly documented linkages—particularly when communication is delayed.

Gaps in the linkage landscape

Three gaps emerged recurring from our discussions:

Roles and responsibilities

Who is responsible for ensuring data quality? Data owners may handle qualitative cleaning; linkers oversee methods and parameters; analysts assess “research readiness”; Funders decide on evidence priorities and set feasibility expectations, while the public must be properly included and represented. Yet, responsibilities remain blurred. Our participants highlighted that while many have direct experience managing sampling bias, there is much less clarity around pre-processing, methodological, or data quality biases—and crucially, whose role it is to address them. This lack of ownership, combined with under-utilisation of existing guidelines (RECORD, GUILD Statement), results in uneven standards and confusion about what is considered minimum.

What belongs in a linkage report?

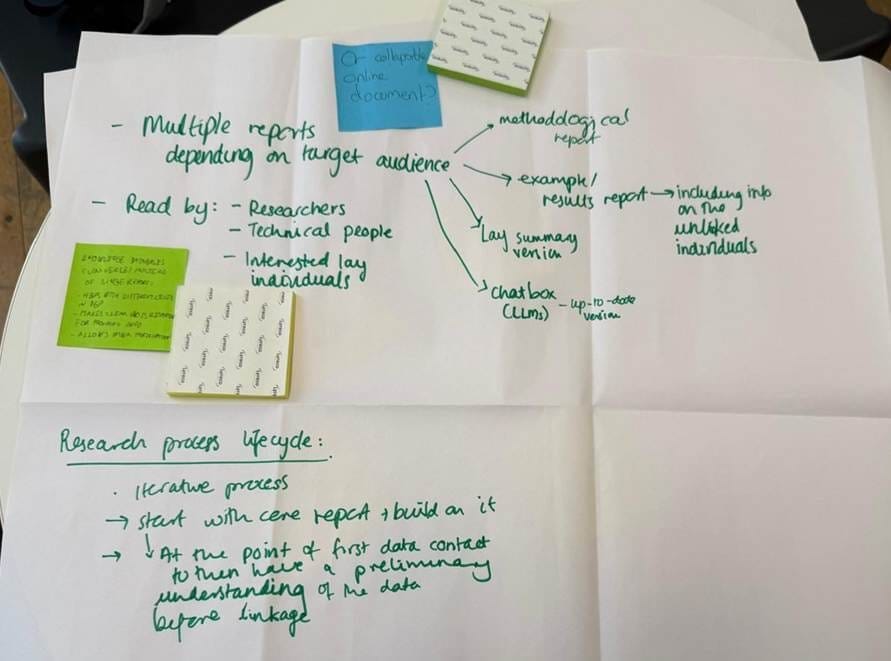

In our group discussion, which brought together linkers, data owners, and analysts, several surprises emerged. When we shared examples of linkage reports, linkers assumed that users would want detailed methodological specifications. Instead, users emphasised their need for contextualised support in understanding how linkage bias or methodological choices might affect their specific research questions. This points to a deeper challenge: linkage is often conducted upstream of any given project, with limited scope for adaptation once automated pipelines are in place.

Researchers need clear, transparent, and usable information—but in what form? A one-size-fits-all approach may not work. Should reports be static or interactive, human-readable or machine-readable, tailored or generic? Needs differ across contexts. Without clarity on roles, expectations often drift, leaving linkers unsure what to produce and analysts unsure how to interpret what they receive.

Do we need one report? Multiple report? Who is it for? Thought-provoking discussion at the pre-conference workshop.

Assessing linkage quality

A common difficulty for linkage quality assessment is the absence of ground truth, making it hard to evaluate whether records have been linked correctly. In practice, most of our commonly used metrics focus on aggregate statistical properties of linked datasets—such as match rates, coverage, or distributional balance across key variables—rather than whether individual records have been linked correctly or incorrectly. These measures can suggest that linkage quality is “good enough” at the population level, even while concealing systematic errors at the person level. For researchers, this means that biases affecting small subgroups, or those relevant to specific research questions, may remain hidden. For data owners and clinicians, it raises the issue of whether metrics designed for statistical research are appropriate when linkage outputs are increasingly used in service delivery or patient-level decision-making.

These technical uncertainties are compounded by the lack of a clear feedback loop, leaving both data producers and users unsure how identified biases should translate into action. Without clear routes for responsibility and accountability, risks persist—not only for scientific inference but also for equity and trust in public data use.

Finally, participants emphasised the importance of embedding public engagement within current processes, rather than treating it as an add-on. If blind spots in linkage pipelines are to be recognised and addressed, the perspectives of those whose data are being linked must inform both methodological development and governance.

Next steps: Building ITALO

We are pleased to announce that DARE UK has awarded funding to ITALO (Improving Transparency Around Linkage Outputs) to take forward the work initiated at this workshop. DARE UK has also support the initiation of SPRINT (Single Patient Record Integrity, Trust & Transparency (SPRINT), a working group within ITALO, in collaboration with NHS England to support NHS England linkage infrastructure and indexing services. This investment will enable us to strengthen transparency, accountability, and engagement around data linkage across the UK. We are also pleased to hear that DARE UK is supporting the formation of UK Data Linkage interest group (lead by Dr Mike Edwards) to encourage wider communications and community engagement! Looking forward to the growth of our lively community!

Example Interest group activities:

- Knowledge sharing – creating space for open exchange on linkage practices, linkage qualities, use of data and communication strategies.

- Expert consensus on roles and responsibilities – bringing together data owners, linkers, analysts, funders, and the public to clarify who should do what, and when, in the linkage lifecycle.

Example Working group activities:

- Linkage quality assessment and reporting – developing practical formats for reporting, in collaboration with NHS England, ONS, and the Splink developer community.

- Public engagement – on developing language or toolkit around communicating risk and benefits of data linkage for clinical service and research.

Public engagement lies at the heart of our interest group and working group activities. We will introduce our wonderful public co-chairs Farheen and Georgina for ITALO and SPRINT separately! It is essential to co-develop approaches to communicate linkage methods and risks in ways that are both accurate and accessible.

Towards a more trustworthy data infrastructure

The ADR UK mission is to enrich the UK’s data assets for the public good. Achieving this requires attention not only to technical linkage challenges but also to their social determinants: which populations are represented, whose voices shape standards, and how findings are communicated back into the system.

With DARE UK’s support, ITALO will provide a collaborative forum to bridge these gaps. By embedding transparency, accountability, and public engagement into the heart of the data-to-evidence pipeline, we take an important step toward more inclusive, valid, and trustworthy research.

Find out more about ITALO and how to get involved:

- Latest updates and events: DARE UK ITALO community group page

- Email ich.italo@ucl.ac.uk to be added to the ITALO mailing list